The Macquarie Era

Period covered by this chapter - 1st January 1810 to 30th November 1821

Governor of the Macquarie era

1st January, 1810 to 30th November, 1821: Colonel Lachlan Macquarie (later Major-General), Governor.

Lachlan Macquarie arrived in Sydney from England on 28th December 1809 with his wife Elizabeth, replacing Captain William Bligh who had been relieved of his duties as Governor-in-Chief of NSW in the Rum Rebellion on 26th January, 1808. A Scotsman of youthful energy and competence and a carpenter by trade, Macquarie was New South Wales longest serving Governor and made more impact on the colony than any other. From the day he stepped ashore he treated Sydney not just as a penal colony but as a settled farming community and channelled all his energies into its growth and development. His predecessors had all been naval men who, apart from Phillip, viewed the settlement as nothing more than a naval base with convicts as the non-enlisted labour force, but such was not the case. Free settlers, most of whom were convicts who had long since completed their sentences, far outnumbered the convicts, but they had continued to be treated as prisoners and second class citizens after their emancipation. They were a people struggling for survival with no hope, no civic pride and no future. Macquarie was determined to change all that. He had considerable experience of colonial life in America and India and firmly believed the success of the young colony depended on its commercial prosperity.

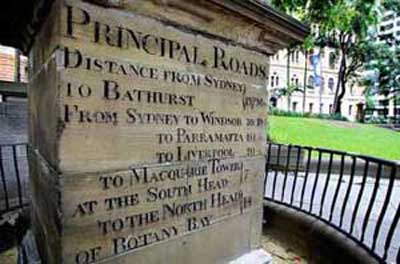

Lachlan Macquarie arrived in Sydney from England on 28th December 1809 with his wife Elizabeth, replacing Captain William Bligh who had been relieved of his duties as Governor-in-Chief of NSW in the Rum Rebellion on 26th January, 1808. A Scotsman of youthful energy and competence and a carpenter by trade, Macquarie was New South Wales longest serving Governor and made more impact on the colony than any other. From the day he stepped ashore he treated Sydney not just as a penal colony but as a settled farming community and channelled all his energies into its growth and development. His predecessors had all been naval men who, apart from Phillip, viewed the settlement as nothing more than a naval base with convicts as the non-enlisted labour force, but such was not the case. Free settlers, most of whom were convicts who had long since completed their sentences, far outnumbered the convicts, but they had continued to be treated as prisoners and second class citizens after their emancipation. They were a people struggling for survival with no hope, no civic pride and no future. Macquarie was determined to change all that. He had considerable experience of colonial life in America and India and firmly believed the success of the young colony depended on its commercial prosperity. Macquarie was appalled at the state of shameful dilapidation of Sydney. He immediately set about restoring order, beginning with the introduction of systematic naming of streets, dropping the use of terms like row and alley. Sgt. Majors Row - it was also known as Tank Stream Row and High Street - became George Street, Governors Row became Bridge Street, Stream Row became Pitt Street. Macquarie closed off many little-used thoroughfares, and widened others (he doubled the width of Pitt Street) discouraging the common practice of cutting through the bush rather than using the road to go from one place to another. Typical of Macquarie's attempts to bring order to the town was his ruling that any stock found wandering in Hyde Park would be confiscated. Another was the erection of an obelisk in Macquarie Place from which all distances within the colony of New South Wales were to be measured. Distances from Sydney to towns and cities all over Australia are still measured from the obelisk today.

The use of rum as the main currency, not to mention the grip on the colonys economy held by the military and landowners through their control of its trade, irked Macquarie. To avoid a repetition of what happened to Bligh when he had tried to break this stranglehold, Macquarie imported 40,000 Spanish dollars in 1813 for use as local currency. He set up a small mint in Bridge Street where a convict named William Henshaw counter stamped the coins and punched out their centres, creating Australias first official currency - the holey dollar and the dump. These coins were quickly circulated throughout the colony and remained in use until 1829.

In the years between the governorships of Phillip and Macquarie, relationships between the white and Aboriginal communities had fallen rapidly into decline. King had made an attempt to improve relations but he was not in the post long enough for his efforts to have had a lasting effect. Macquarie made genuine moves to help the Aborigines who, by the time he came to office, had very much become downtrodden outcasts dwelling on the outskirts of the colony who had been left to fend for themselves. Macquarie's efforts to bring reconciliation to the two communities were noble, in spite of being viewed today by many as nothing more than an attempt to Europeanise the natives and purge them of their Aboriginality. But in his day, given the commonly held belief that Aborigines were savages of a lower intelligence than the whites, his treatment of them was very progressive.

It was Macquarie who created Australias first Aboriginal reserve. Located at Wooloomooloo, it was run by the Aboriginal community who lived there. Whites were only permitted to enter it by invitation of its residents. The reserve was commonly known as Blacktown in spite of Macquarie having named it Hemnrietta Town, after Mrs Macquarie who was instrumental in ita establishment. After Macquarie's departure, Gov. Darling, believing the location of an Aboriginal reserve so close to the white community was inappropriate, shifted it to La Perouse and subdivided the land which the reserve occupied for the development of upper class residences.

Macquarie also gave a large portion of land at Middle Head to a North Shore Aboriginal clan. He attempted to help them assimilate into the Sydney community by teaching them about farming and agriculture but to no avail. The Aborigines were unable to adapt to the ways of the white man and drifted away from Middle Head to return to their tribal lands and traditional way of life. Macquarie's term of office coincided with a substantial increase in the number of convicts sent to the colony. Whenever a new shipment of convicts arrived he would head for the wharves where he would personally greet them, take stock of who had arrived and what skills they had, and hand pick for government service any who he believed had particular skills required to fulfill his special projects. They became the workforce he used to create his Sydney and bring about the civic pride the colonists so desperately lacked. He utilised the new arrivals in ambitious public works programmes which not only helped to absorb their numbers, but allowed him to extend the ticket-of-leave system in which convicts were hired out to settlers to assist them in their trades and businesses. He encouraged the reformation of convicts by offering emancipation for good behaviour and employed many of them in positions of authority.

Macquarie's public works programmes included enlarging and improving the road system; the instigation of a grid pattern of streets for the developing southern end of Sydney town; the construction of a number of civic buildings which included the Hyde Park Barracks, The Rum Hospital, The Windsor Courthouse and The South Head lighthouse; the establishment of a number of country towns - Castlereagh, Richmond, Wilberforce, Pitt Town and Windsor, Liverpool, Campbelltown and Bathurst - and the development of the Botanical Gardens, The Domain and Hyde Park. The latter, located alongside his planned town square and convict barracks, was part of a large tract of land earmarked by Phillip in 1788 for public recreation. Macquarie encouraged the development of a 10 furlong racetrack (the parks circular shape at its northern end is a reminder of this former activity) and it was here that, by accident, the tradition in NSW and Queensland of racing in a clockwise direction commenced. Macquarie opened Sydneys first ever Spring Horse Racing Carnival, held at the newly developed Hyde Park Race Track in October 1810. A young William Charles Wentworth, the son of Dr. DArcy Wentworth who would later work at the Rum Hospital to be built nearby a few years later, thrilled spectators with his winning ride in the saddle of the bay gelding, Gig. On that occasion, a friendship was forged between them. Three years on, the young Wentworth was a member of the first party to cross the Blue Mountains.

After Macquarie's return to London it was Wentworth who followed him to clear his name after it had been muddied. The race of 1810 was the first of many sporting events that would be held in Hyde Park over the years. Horse racing continued until the late 1820s, by which time the park had become a regular venue for fairs, knuckle fighting, boxing and wrestling. A cricket field was created within its boundaries in the 1830s and continued in use until its transfer to the Domain in 1862, the year in which the first cricket match between England and New South Wales took place there. Hyde Park became the location for Sydneys first zoo in 1849 and featured elephants, bears and a tiger in its collection.

One of Macquarie's keenest supporters was his wife Elizabeth who was actively involved in her husbands public works programmes and was responsible for the selection of many of the designs of her husbands buildings which she lifted from a collection of building design books she brought with her. Though his drive and ambition was admired by the emancipists who gave him almost godlike status, Macquarie encountered much opposition, particularly among the wealthier colonists. The military personnel who in the early days had been employed to oversee the convicts, resented their former Òslaves being given equal rights and that Macquarie kept the best of the new arrivals for public service duties. To them Macquarie's attempts to turn the penal settlement into a modern town was nothing more than an extravagant waste of public resources. His domineering, stubborn attitude did nothing to win their friendship or support and it was only a matter of time before a major confrontation would bring their differences of opinion to a head.

His attitude towards his superiors in England reflected a similar arrogance, though he was careful to hide it from them so as to maintain their support. Macquarie knew what he wanted and wasnt afraid to bend the rules or deliberately misinterpret his instructions from the British Government when they refused his requests. Most such occasions involved either the spending of public money or making Sydney more like a town and less like a goal. For example, when his request to start a bank was refused, he went ahead with the plan anyway, but rather than establish it with government funds, he did it by public subscription, he and his wife being two of the six founding shareholders. Six months after it was established, he wrote to his superiors in England, advising them that the free settlers had started their own bank and that as it was running so successfully, it would be unwise for the Government not to be involved as it might precipitate another Rum Rebellion.

Macquarie's governorship, along with his health, went into a noticeable decline following the arrival of Jeffrey Hart Bent, the judge of Macquarie's newly-established Supreme Court, which opened for business on 28th July 1814. Both men saw themselves as the ultimate mouthpiece of law and authority in the colony and their constant clashes began not only to erode Macquarie's position of authority but precipitated the unification of Macquarie's enemies and the consolidation of support for his removal. So strong did the division in the community towards him grow, a number of gentry who had friends in English political circles began to use their influence against him, resulting in Macquarie having to face a commission of enquiry into his administration headed by Commissioner John T. Bigge. Whilst there is no concrete evidence that he was paid by the wealthy free men of the colony to get rid of Macquarie, Bigge's report was clearly greatly influenced by them. It was a scathing report that was neither unbiased or fair and contained many inaccuracies and exaggerations which could almost be described as lies. As a result of Bigges report, Macquarie was ordered to curtail many of his public works programmes. The frustration and pressure on Macquarie led to recurring bouts of illness. He made three requests to leave Sydney, his resignation finally being accepted in 1822.

Macquarie's attempt to clear his name when he returned to England largely fell on deaf ears. Bigges report had already been published and accepted as fact, Macquarie's report was not widely circulated and he had to fight for the pension he so richly deserved. He died in relative poverty at 49 Duke Street, St. James, London, on 1 July 1824, but not after some justice had been done. William Charles Wentworth was so disturbed by the way Macquarie had been treated, he followed Macquarie to England where he used his considerable influence to clear Macquarie's name and show how biased and inaccurate Bigge's report had been. The day before he died, Macquarie was visited by Wentworth who told him he had been successful in getting the British Government to endorse a cause Macquarie had championed for so long - the granting of full rights to all emancipists throughout the British Empire.

Wentworth returned to Sydney immediately, bringing news of Macquarie's death. So saddened were the common folk, a day of mourning was proclaimed and plans were formulated to build a memorial to Macquarie to be financed by public subscription. Though the memorial was never built, time would show that Sydney did not need a monument to keep the memory of Lachlan Macquarie alive. Sydney itself would become a memorial to its most loved and respected Colonial Governor. His influence is still visible in the bustling streets of what was upon his arrival little more than a bush camp, but which he singlehandedly had nurtured into a thriving community. Of all the early Governors of New South Wales, none left so indelible mark upon the place and he is totally forgiven for his enthusiasm in naming so many places after himself. During his 11 years in Sydney, he had overseen 256 items of construction, many of which remain today. They included 67 public buildings in Sydney town, 20 at Parramatta, 15 at Windsor and 12 at Windsor, not to mention those in Bathurst and Hobart. He set in motion the creation of the Argyle Cut in The Rocks (though work did not commence until 1843).

He oversaw the building of 14 public roads, the development of wharves on Cockle Bay, the development of shipbuilding yards on Sydney Cove, the installation of the first steam driven mill and the opening of Australia's first bank. Macquarie also played a major role in the development of Hobart. During his governorship, the population of Sydney grew from 11,590 to 38,798. Animal numbers grew also, the total sheep flock rising from 26,000 to around 290,000. Cattle increased from 12,442 head to 109,939 and pigs increased from 9,544 to 33,906. The area of land under agriculture rose from 3,030 ha to 13,720 ha.

Macquarie summarised his contribution towards the development of Sydney in his report to Earl Bathurst, London, dated 27 July 1822, thus: I found the colony barely emerging from infantile imbecility, and suffering from various privations and disabilities; the country impenetrable from beyond 40 miles of Sydney ... the few road sand bridges, formerly constructions, rendered almost impassable ... I left it ... reaping incalculable advantages from my extensive and important discoveries in all directions. This change may indeed by ascribed in part to the natural operation of time and events on individual enterprise. How far it may be attributed to matters originating with myself, ... and my zeal and judgment in giving effect to my instructions, I humbly submit to His Majesty and His Ministers.

It was during Macquarie's term of office that Sydney's system of major roads that are still in use today was put into place. Parramatta Road had already been established, but roads to other parts of the colony had not been clearly defined and many were little more than tracks through the bush. Macquarie's first road building work was South Head Road (part of which is now Oxford Street) which linked Sydney to the pilot station and settlement at Watsons Bay, replacing a rough track cut through the bush by the colonial surgeon John Harris in 1803. Built by 21 men of the 73rd Regiment, it was the first of many roads built by Macquarie to be financed by public subscription. The Governor contended that, as local residents would be the only beneficiaries from the construction of good roads in their districts, they should be preparedvto assist in the cost of their implementation. Completion of the road saw further land grants in the area: Bondi in 1810; Rose Bay in 1812; Double Bay in 1821. These grants led to the creation of New South Head Road which took a shorter route, but its construction was not commenced until 1831 and completed some four years later.

Having surveyed the site of the town of Liverpool in the year previous, Macquarie began work on a road to the new town in April 1813. The contract for the building of the Liverpool Road was given to William Roberts, an illiterate ex-convict who had impressed Macquarie when supervising road restoration works on George and Bridge Streets. Liverpool Road was 24 kilometres in length and followed a number of Aboriginal paths. It required the building of 27 bridges along the way and was opened to traffic on 22 February 1814. So happy was Macquarie with Roberts work, he was employed to extend the Sydney to Parramatta road to Windsor (completed April 1814), to build a road from Liverpool to Parramatta (Woodville Road) as well as the Airds, Bringelly, Minto and Cowpasture Roads and their associated 28 bridges.

It was Macquarie's drive to discover what lay on the other side of the Blue Mountains that led to the first colonial crossing in 1813 by Blaxland, Lawson and Wentworth. He wasted no time in building a road along the route taken by the pioneers, sending a crew to complete the task hot on the heels of the trailblazers. Nepean district builder William Cox was placed in charge of its construction, which was commissioned in April 1815. The opening of the section from Emu Ford to Mt York. Cox saw the completion of 202km of road in just six months using only 60 convict workers and overseers.

Major George Druitt of the 48th Regiment was appointed Inspector of Government Public Works in December 1817. At the end of his term, Druitt recorded that with a workforce of 3,117 men, he had completed the following:

Sydney to Macquarie Tower, South Island (Bear Island, La Perouse) - 13 kilometres, 6 bridges

Sydney to Waterloo Mill - Botany Bay Road - 3.3 kilometres, 6 bridges

Sydney to Parramatta - Parramatta Road - 24 kilometres, 14 bridges

Parramatta to Liverpool - Woodville Road - 8 kilometres, 8 bridges

Parramatta to Windsor - Old Windsor Road - 32 kilometres, 70 bridges (extended as far as St. Albans)

Campbelltown to Appin - Appin Road - 5 kilometres, 5 bridges

Sydney to Liverpool - Liverpool Road - 32 kilometres, 27 bridges

Sydney to South Head - South Head Road (Oxford Street) - 8 kilometres, 4 kilometres

Billy Blue

In 1807, a former convict named Billy Blue had been appointed Sydneys first and only Waterman, a position which gave him exclusive rights to operate a ferry service on the harbour. Of Jamaican descent, Blue was transported to NSW in 1807 for stealing a bag of sugar. After emancipation, he was granted 80 acres on Blues Point (then known as Murdering Point), from which he operated a ferry service to Millers Point. A colourful, eccentric character, he liked to dress in outlandish military uniforms which earned him the nickname of the Old Commodore of the Fleet by Gov. Macquarie. At its peak, his business operated 11 boats and employed Billy, his son and three convicts. He died age 82. Blues Point and the Commodore Hotel, built by his descendants, recall this earlier pioneer of boat travel on Sydney Harbour.

Lavender Bay recalls George Lavender, an early resident of the lower north shore who, like his father-in-law, Billy Blue, became a boatman, and operated a ferry service across the harbour in the 1830s and 40s. During the Macquarie years, the main customers of the lower north shore ferry service were timbergetters whose activities centred around a government saw-pit established in 1813 on the Lane Cove River. Logging was the major activity in the area during the first half of the 19th century as it was originally covered with huge blue gum forests.

Harbour Bridge

Ever since the establishment of the colony of Sydney, its occupants have dreamed of a bridge or a series of bridges to connect the north and south shores. The diary of First Fleeter William Dawes records that even as he was establishing his observatory on the point which bears his name, Dawes gazed across the harbour towards the north shore in February 1788 and realised that one day a bridge would have to span the harbour, perhaps at a point such as this. What would his reaction be if he could come back today and see the realisation of his dream - The Sydney Harbour Bridge? So convinced was he of the future need for such a bridge, he included a proposal for one in the notes which accompanied his first survey of the town of Sydney.Governor Macquarie had similar ideas and in 1817 he had Colonial Architect Francis Greenway come up with ways of building a bridge from Dawes Point to Milsons Point. Greenway apparently did this, though records of his suggestions have not survived. As both the finance and the technology to complete such a project were in extreme short supply, nothing eventuated and the idea was left for future generations to bring to fruition.

Fort Macquarie

Though Macquarie, like all the Governors before him, was a military man, there is little evidence to suggest he made any major contribution towards the defence of Sydney other than upgrading the fort on Dawes Point and building Fort Macquarie on Bennelong Point which replaced a small fort established by First Fleeter William Dawes in 1788. Francis Greenway, Macquarie's buddy in arms when it came to the erection of public buildings in Sydney, designed the fort which came into use in January 1821, just a short while before Macquarie's departure from NSW.

Fort Macquarie was a large, impressive structure built of stone hewn from an outcrop of rock near the construction site. So much stone was required for the project, a sheer vertical rock face was left at the quarry site on completion. The rock face became known as the Tarpeian Rock, a classical allusion to the precipitous Capiotoline Hill in Rome from which, in the time of the Caesars, criminals were hurled to their deaths. By the turn of the 20th century, Fort Macquarie had outlived its usefulness. In 1902, it was replaced by the Fort Macquarie Tram Depot, a terminus and workshops for the Belmore to Circular Quay electric tram service which came down Castlereagh and Bligh Streets.

By the time of the arrival of Gov. Macquarie, most if not all the makeshift humpies built in 1788 had been replaced by more substantial yet still rather spartan dwellings and business houses. This second generation of buildings, though more solid than the first, were still rudimentary in construction and design. Only a handful of stone cottages in outlying districts survive from this era. The high standards set by Macquarie in the public buildings he had erected were the catalyst for new standards in private dwellings and commercial building construction utilising the excellent sandstone that was in plenteous supply throughout the Sydney basin.

Macquarie's enthusiasm attracted a number of architects to come forward, including Francis Howard Greenway (right), a convict transported for forgery who came with a recommendation of none other than Gov. Phillip. He had arrived in 1814 in the same year as two other architects - John Watts and Henry Kitchen. Macquarie tried all three - Watts supervised the additions to Old Government House at Parramatta and Kitchen was involved in the construction of the Parramatta Weir. Greenway was found to be by far the best, his family in Bristol having been quarry men, stonemasons and builders for many generations. Had it not been for Greenways overbearing, pushy manner, which for some reason appealed to Macquarie and sparked a strong working relationship between them, Greenway would have remained Colonial Architect for much longer than the nine years he served. Had this happened he would have left behind an even greater legacy of architectural work than he did. His public buildings have all survived though none of the residences he designed after his dismissal from official duties remain.

Macquarie's enthusiasm attracted a number of architects to come forward, including Francis Howard Greenway (right), a convict transported for forgery who came with a recommendation of none other than Gov. Phillip. He had arrived in 1814 in the same year as two other architects - John Watts and Henry Kitchen. Macquarie tried all three - Watts supervised the additions to Old Government House at Parramatta and Kitchen was involved in the construction of the Parramatta Weir. Greenway was found to be by far the best, his family in Bristol having been quarry men, stonemasons and builders for many generations. Had it not been for Greenways overbearing, pushy manner, which for some reason appealed to Macquarie and sparked a strong working relationship between them, Greenway would have remained Colonial Architect for much longer than the nine years he served. Had this happened he would have left behind an even greater legacy of architectural work than he did. His public buildings have all survived though none of the residences he designed after his dismissal from official duties remain.Colonial Georgian

Whilst John Harris's Experiment Farm at Parramatta was typical of the simple farmhouses that would proliferate the colony during the first five decades, the streetscapes of Sydney Town and Parramatta around the turn of the 19th century were taking on a different look. The new buildings reflected the architectural styles of Europe being introduced by new arrivals from Mother England who brought with them the skills in building design and construction that the colony so desperately needed.The predominant style of the day was Georgian, which refers to the reigns of the four kings of England named George between the years 1714-1830, the period in which this style flourished. Sydney and Hobart are where most of Australias surviving Georgian architecture can be observed as few of Australias other capital cities had been founded during the Georgian era and those which had were still in their infancy.

Examples:

NSW Parliament House, Macquarie Street, Sydney (1814)

The Mint Museum, Macquarie Street, Sydney (1814)

Cadmans Cottage, George Street, Sydney (1816; Francis Greenway?)

Kirkham Stables, Kirkham Lane, Narellan (1816)

Rouse Hill House, Windsor Rd, Rouse Hill (1818)

Former Female Orphans School, Rydalmere Ho

spital, Rydalmere (1818)

Hyde Park Barracks, Macquarie St, Sydney (1819; Francis Greenway)

NSW Supreme Court Building, Elizabeth Street, Sydney (1819; Francis Greenway)

Juniper Hall, 250 Oxford Street, Paddington (1820 - 22)

St James Church, 179 King Street, Sydney (1822; Francis Greenway)

Windsor Courthouse, Court Street, Windsor (1822; Francis Greenway)

Judge's House

Regency

An expression of the Georgian style which came to signify the refined taste of the British upper classes. The Regency period - during which the Prince of Wales ruled as regent during his fathers madness - extended from 1811 to 1820, but the style was popular throughout the first four decades of the 19th century.Characterisics:

Added a touch of elegance to the Georgian style with the use of gentle projections and recessions, Porticos, balconies, and stucco (plaster applied to outside walls) often painted to look like stone. Timber, wrought iron and cast iron decoration was occasionally used, as were slate and sheet metal roof tiles, the latter being a product of the industrial revolution.

Examples:

National Trust Centre, Observatory Hill, Sydney (1815; J.C. Watts)

St Matthews Church, Greenway Crescent, Windsor (1820; Francis Greenway)

Cadmans Cottage

1816 - Cadmans Cottage, George Street, The Rocks

The oldest surviving residence in the City of Sydney, this four-room sandstone cottage was built to house the Governors boat crew and is very much a basic, no-frills colonial cottage. In 1827, it became the home of the Governor Boats Superintendent, John Cadman, a former convict, after whom it is named. Originally a single storey house, the second storey was added during the 1850s. The stone wall at the rear of the cottage below George Street was erected at the same time as the cottage.

1820-22 - Juniper Hall, 250 Oxford Street, Paddington

The first residence in the area now known as Paddington, this fine example of Colonial Georgian architecture was the home of Robert Cooper, an emancipists who made his fortune as a gin distiller. Believed to be the largest residence ever built in the district (it needed to be large as Cooper had 28 children), it was saved from demolition in the 1980s and is now a restored to its former glory and used as offices. Juniper Hall was built some 20 years before the Victoria Barracks, the construction of which was the catalyst to the area being opened up as a working class residential area.

1821-22 - The Judges House, 312 Kent Street, Sydney

The cottage was designed and built by William Harper, a Scottish migrant who worked as an Assistant Surveyor. Ill health and eventual blindness caused him to retire when still young and his home was rented to Supreme Court Judge Justice James Dowling (after whom Dowling Street was named) at an annual rental of 200 pounds. The house once enjoyed 'delightful and healthful views of Darling Harbour'. It was described as having Ôa large garden at the back, the property being surrounded by paddocks.

Parliament House

1811 - 1816 - Parliament House, Macquarie Street, Sydney

The seat of government of New South Wales since 1829, the central section of Parliament House was built between 1811 and 1814 as part of the original Sydney Hospital. Its designer is unknown, but the concept most likely came from a pattern book of elegant home designs belonging to Governor Macquarie's wife, Elizabeth. The entrepreneurs who paid for and supervised its construction in exchange for the right to import rum into the colony for 3 years were Alexander Riley, Garnham Blaxcell and D'Arcy Wentworth. All the government had to supply were eighty oxen (for slaughter), twenty draught bullocks and twenty convict labourers. Macquarie wrote glowingly of his scheme in his request to the Colonial Secretary, Lord Liverpool, for permission to proceed with the project. Liverpool turned it down, but by the time news of his decision reached Sydney, Macquarie had made sure construction was sufficiently advanced that it had passed the point of no return.Unfortunately, the financiers of the hospital had little building experience, and the buildings were so badly made, it led Macquarie to vow never again to finance a public building in this manner again. When it was handed over on completion, Macquarie noticed it was two feet lower than marked on the plan so he made the contractors provide labour for other public works to the value of the work not done on the Hospital befored paying them out. The builders had also used stone-faaced rubble rather than solid stone and the roof framing design was faulty. When Francis Greenway arrived in Sydney in 1816, Macquarie tested his skills by employing him to rectify the faults. Greenway so impressed Macquarie, he employed him as full time Colonial Architect.

In 1829 Governor Darling appropriated the northern wing of the hospital to accommodate the Legislative and Executive Councils. The southern wing of the building, which features a cast-iron facade, is a later addition. Prefabricated in England, it was originally destined for the Goldfields near Bathurst as a chapel, however on its arrival in Sydney, it was reassigned as the new chamber for the Legislative Council. The packing cases in which the prefabricated kit arrived were used to line the chamber, the rough timber is still on view today.

1811 - 1816, 1879 - 1894 - Sydney Hospital, Macquarie Street, Sydney

Originally known as the Rum Hospital because its builders were allowed to export rum for resale, the Sydney Hospital once occupied a number of buildings on this sight. The northern wing is now Parliament House, the Southern wing is occupied by the Sydney Mint Museum. By the 1870s, the central section, which had been erected on poor foundations, was in danger of collapse and had to be demolished. It was replaced by new buildings which continue to function as a hospital today. These newer buildings are of Classic Revival style and the one which fronts onto Macquarie Street boast floral stained-glass windows and a Baroque staircase in the entrance hall. These fine specimens of Victorian architecture were created out of Pyrmont sandstone and feature arcaded verandahs with ornate balustrading. One of two domed former gatehouses has functioned as a tiny corner store.

1811 - 1816 - Sydney Mint Museum, Macquarie Street, Sydney

The Sydney Mint took over the south wing of the Rum Hospital in 1854 following the discovery of gold and until 1927 all gold found in New South Wales was turned into bullion and currency here. After decades of use and misuse as everything from Government offices to a car park, this building, a twin to Government House a few doors away, was restored and in 1982, opened as a branch of the Powerhouse Museum. Restoration included a replica of the buildings original wooden roof made of she-oak (caesarean) shingles.

1815 (?) - Shipwrights Arms, 75 Windmill Street, Millers Point

Though no records exist to verify the exact year of its construction, this two storey brick house dates from the Macquarie period as it was built as a residence for a free settler who arrived in the colony in 1815. The sandstone used for its foundations came from the nearby Kent Street Quarry which was a major source of sandstone for building constructed in the western end of Sydney during the Macquarie era. Its identity as one of five pubs in The Rocks to be called Shipwrights Arms had been lost until its restoration in 1968 when countless layers of paint were removed to reveal its former use. John Clarke, its first licencee, operated the pub between 1833 and 1837.

Sydney Conservatorium of Music